Venezuela's Descent Into World's Riskiest Sovereign Credit: Q&A

by- No country is more likely to miss payments, swaps prices show

- Investors pricing in chance of overseas default in October

Venezuela is running out of money.

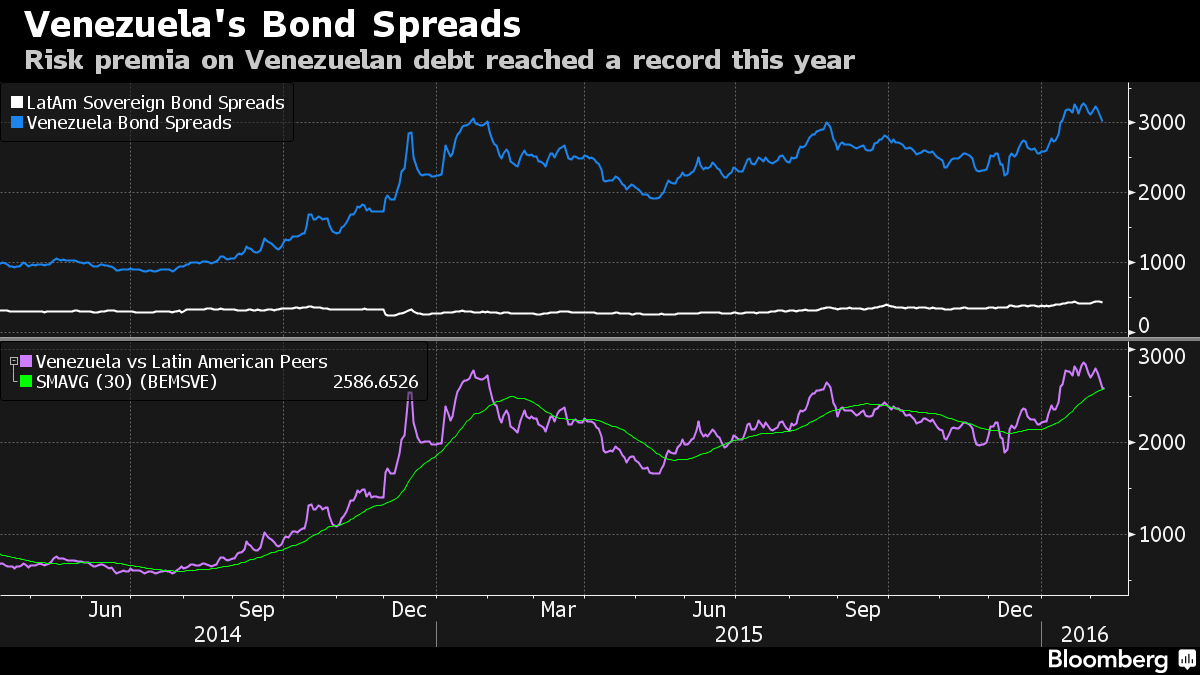

The price of oil, which makes up almost all of the country’s exports, has tumbled 75 percent in the past three years and investors are predicting the country is on course for the biggest-ever emerging-market sovereign default. No nation in the world is more likely to miss payments, according to traders of its credit-default swaps.

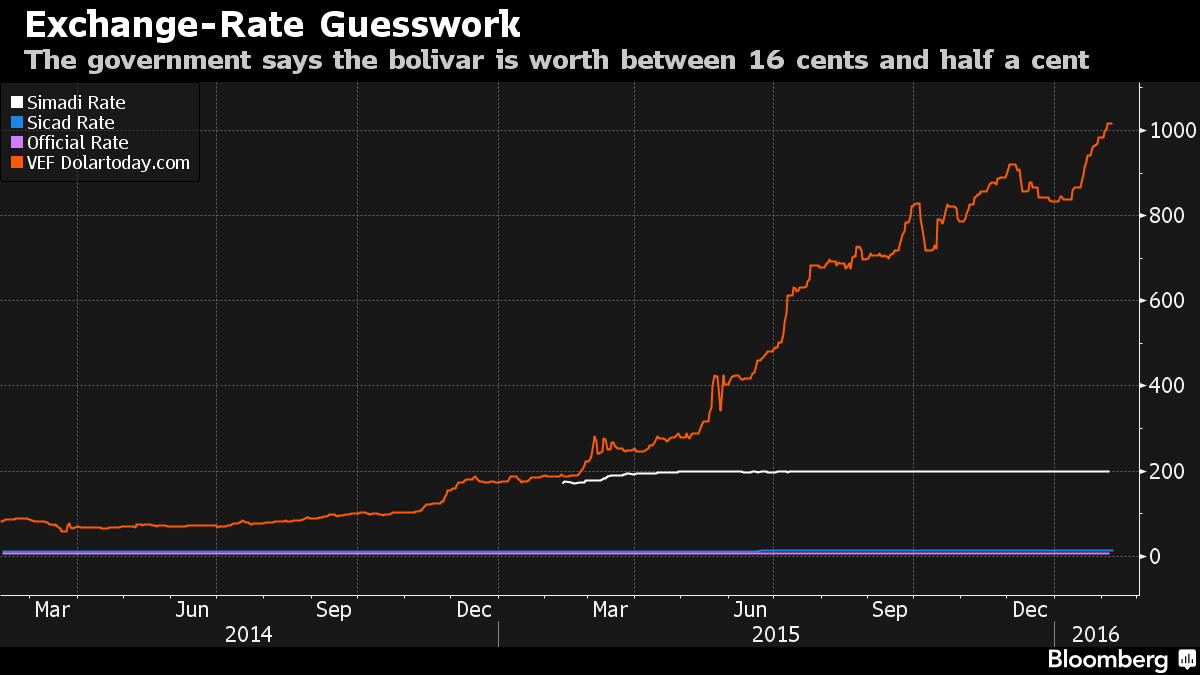

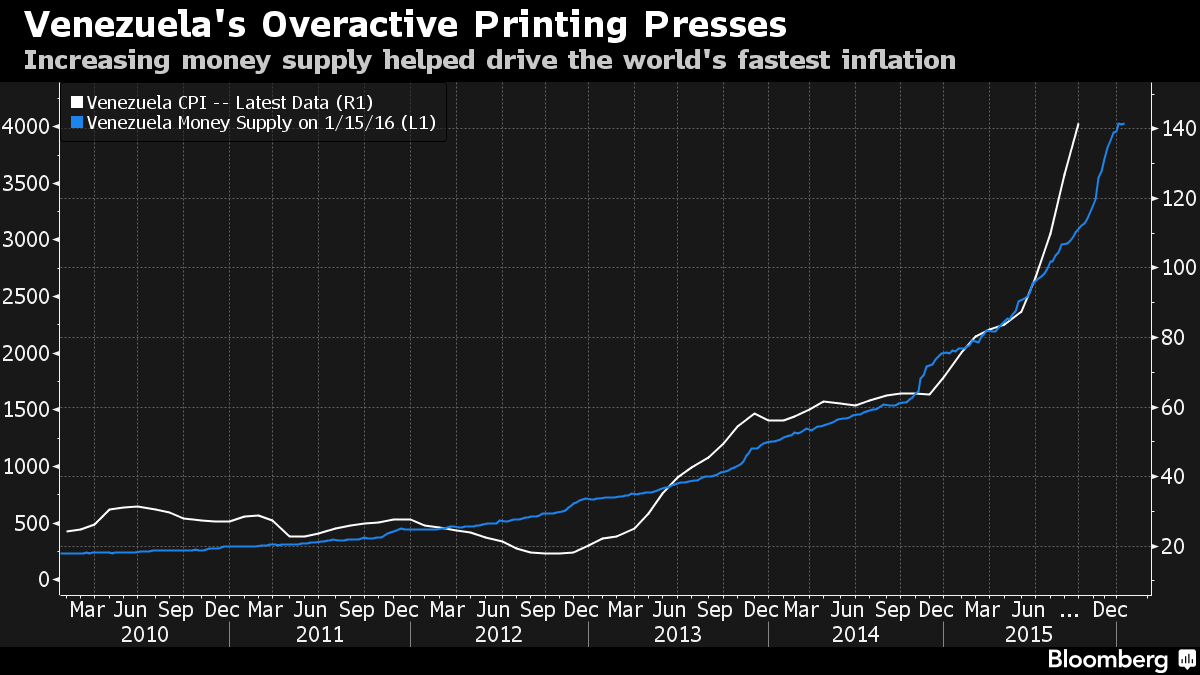

The country already tops measures of the world’s most miserable economy, with inflation of almost 100 percent last year, a currency that has collapsed on the black market to less than 1 percent of its official value and shortages of basic goods such as detergent and antibiotics. It’s a horrific turnaround for what was once one of the region’s most stable democracies, famous for its big cars, cheap gasoline and beauty queens.

While bond prices suggest that most investors are confident the country will make good on a $1.5 billion obligation coming due Feb. 26, the outlook dims for $4.1 billion of notes the state oil company is due to pay back in October and November.

Here are answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about Venezuela:

How much debt does Venezuela have?

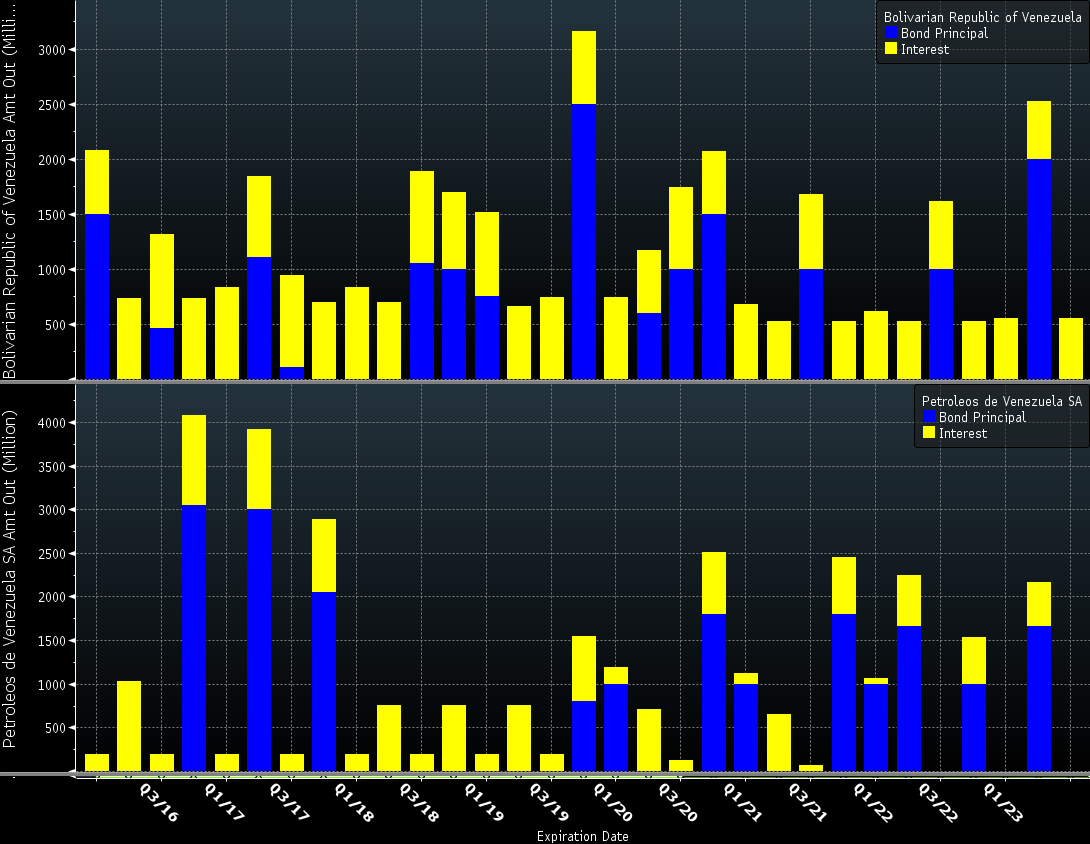

Venezuela has $35.6 billion of dollar bonds outstanding and owes $67 billion once interest payments are included. State-owned oil company Petroleos de Venezuela SA, known as PDVSA, has $33.5 billion of bonds, and $52.6 billion counting interest.

If there’s a default, when is it most likely to come?

Venezuela has the cash to pay back the bonds coming due in February along with $326 million of interest payments this month. In October and November of this year, PDVSA needs to pay back $4.1 billion of bonds and $1 billion in interest. The notes’ price of about 56 cents on the dollar indicate skepticism the country will be able to do that.

Trading in the credit-default swaps market suggests there’s a 76 percent chance Venezuela will default in the next 12 months.

What might the recovery value of the bonds be?

Estimates vary between 20 cents on the dollar and as much as 71 cents in the case of PDVSA bonds. Since Venezuela is so reliant on oil, the value is hugely dependent on the price of crude. Estimates compiled by Bloomberg for the year-end price of West Texas Intermediate range between $38 and $70 a barrel.

Barclays Plc says that recovery values are likely to be higher on bonds from PDVSA.

What overseas assets could investors try to seize?

PDVSA has refineries, tankers and receivables. Of course, the value of the oil assets depends in part on the price of crude. In August last year, Barclays estimated the total at between $8 billion and $10 billion, but that was with oil fetching at least $50 a barrel.

The operating assets of Citgo Holding Inc., PDVSA’s U.S. refining subsidiary, are already pledged to creditors. The unit’s $1.5 billion bonds due in 2020 are secured by a 100 percent equity stake in Citgo Petroleum Corp.

How did things get this bad?

During his 14 years in office, former President Hugo Chavez nationalized companies and expanded the government’s role in the economy. By the time of his death in 2013, domestic industry had been crippled, leaving Venezuela almost entirely dependent on imports for consumer goods. Those imports were paid for with revenue from oil.

The economic model, characterized by government largess and inefficiency, was nonetheless more or less sustainable with oil prices above $100, despite the occasional shortage of toilet paper and the fact that the government had pledged much of its crude output to repay loans from China and in subsidies to regional allies such as Cuba.

As oil prices fell, the government relied more on creating new money to meet its expenses, helping fuel the fastest inflation in the world and making the black-market bolivar the worst-performing currency in the world.

By mid-2014, with oil hovering between $90 and $100, Venezuela was in trouble. President Nicolas Maduro, Chavez’s handpicked successor, could have boosted the country’s income in bolivars by devaluing the official exchange rate of 6.3 per dollar at which it sold much of its hard currency. Yet he postponed the decision -- possibly out of concern for the inflationary impact such a move could have -- in favor of a series of reluctant half measures.

Now, with the country’s oil fetching about $25 a barrel, Venezuela’s crude income will fall toward $22 billion this year, according to Bank of America Corp. That’s barely enough to cover $10 billion of debt service on bonds, $4.3 billion of imports for the oil sector and $6.2 billion of payments on loans from China, the bank wrote in a note Feb. 8.

Unless Maduro slashes government subsidies and devalues the currency, Venezuela won’t have enough dollar income left to pay debt and import food.

Would a default be the biggest ever for a sovereign?

No, it would be the second-biggest. Greece defaulted on $261 billion in March 2012, according to Moody’s Investors Service data. Argentina defaulted on $95 billion in 2001.

Has Venezuela defaulted before?

Ten times on international debt, mostly in the 19th century, according to data from Harvard University economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff. Venezuela first defaulted in 1826, 15 years after declaring independence from Spain.

Most recently, in 2005, it missed payments on bonds linked to oil prices after the government fired striking executives from PDVSA and the resulting chaos meant that the prices needed to calculate the payments weren’t available. The bonds it defaulted on were so-called Brady bonds, which were the result of a debt restructuring following a default in 1990.

How would a Venezuelan default differ from Argentina’s?

With any luck it won’t go on as long. Argentina’s default has dragged on for 14 years as successive governments have defied investors who refused to accept losses of 70 cents on the dollar and fought them in U.S. courts. Venezuela, on the other hand, would probably be motivated to settle sooner in order to free up its oil shipments, according to Nomura.

Venezuela’s bonds have collective-action clauses, which mean that reaching a restructuring agreement with a majority of bondholders would require everyone to go along with the deal. PDVSA notes don’t have that rule. Investors are divided as to whether this makes default on one or the other more likely or easier to resolve.

“Each sovereign default is unique,” Siobhan Morden, the head of Latin American fixed-income strategy at Nomura, wrote in a note to clients in February.

Is there any hope that things can get better?

There’s a case to be made that not all is lost.

First, the government could implement reforms such as cutting subsidies on gasoline or devaluing the currency, which would allow it to stretch its dollar income much further. Bank of America Corp. says it expects Venezuela to make all of this year’s bond payments, as long as it also changes the currency regime, loosens price controls and cuts subsidies.

Second, the political opposition is gaining ground. The opposition won two-thirds of the National Assembly in elections late last year, giving it widespread powers to dismiss ministers, block presidential decrees and block court appointments.

Third, China could appear with new financing. The Asian nation has already lent it about $17 billion and could presumably come to the rescue again.

Fourth, oil prices could rise. The country can scrape by with an average price this year of $50 to $65 a barrel, according to estimates from Barclays, Bank of America and Nomura.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen