These 30-Cent Bonds

Are Barclays's Top Pick in Venezuela Default

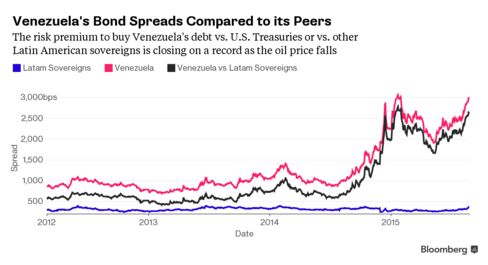

The latest dive in oil prices has become a stark reminder of how perilously close to default Venezuela is in the eyes of debt investors.

Not only have the country’s bonds plunged deeper into distress, but the longer-term debt of its state-owned crude producer has plummeted as low as 30 cents on the dollar.

To Barclays Plc and Exotix Ltd., bond investors in Petroleos de Venezuela SA are underestimating how much money they would be able to recoup after default. In fact, they may be able to get as much as 71 cents on the dollar in a restructuring post-default, assuming higher oil prices and a devaluation, according to Sebastian Vargas, a strategist at Barclays.

“The long end of the PDVSA curve is what will benefit from those higher recovery values,” he said from New York. “That’s the place to be.”

Venezuela is careening toward a default as the slump in crude wreaks havoc on the finances of a country that depends on oil for almost all its export revenue. Venezuela’s oil basket fell to $35 a barrel on Aug. 25, President Nicolas Maduro told reporters Tuesday. That’s the lowest since February 2009.

Credit-default swaps traders put the probability of a Venezuela and PDVSA default by September 2016 at 73 percent, up from 40 percent three months ago.

While the bulk of Venezuela’s bond payments due through 2017 are for PDVSA debt, those securities will have a higher recovery value than those of the sovereign, according to Vargas.

The value of PDVSA’s offshore assets -- including Citgo Petroleum Corp. stations -- has declined after the 60 percent drop in oil prices over the past year, but they still may be worth as much as $10 billion, Barclays estimates. That puts a floor to PDVSA’s recovery value of about 25 cents on the dollar on its $32 billion of debt, and it’s likely that in order to increase participation in a debt swap, PDVSA would boost the recovery value, the London-based bank said in an Aug. 18 report.

That recovery depends on oil prices and “the capacity of the authorities to adjust” policies, according to Barclays. Assuming crude prices between $50 and $75 a barrel, a devaluation of the bolivar from 6.3 per dollar and higher domestic gasoline prices, investors may recover between 45 cents on the dollar and 71 cents, Vargas said. That compares with a range of 29 cents on the dollar to 71 cents for government debt.

Sill, Victor Fu, a strategist at Hapoalim Securities, says that the sovereign’s lower-priced bonds are preferable to PDVSA’s. He recommends Venezuela’s notes due in 2028 and 2034, which trade at 31 cents and 31.75 cents on the dollar, respectively, and are cheaper than similar-maturity debt from the oil producer.

PDVSA’s assets may be more transparent than the government’s, yet Citgo has its own creditors that “should be ranked in higher priority than PDVSA’s creditors,” Fu said in an e-mail. “For domestic assets of the two entities, they are very opaque. It could be argued that in case of stress, Venezuela can try to keep more domestic assets with the sovereign.”

To Exotix Ltd.’s analyst Francisco Velasco, PDVSA bonds due in 2024, 2026, 2027 and 2037 would generate the biggest returns in most default scenarios over the next 12 to 24 months.

Were PDVSA to avoid default until October 2017, bond investors would realize annualized returns of about 10 percent or more in a restructuring, assuming a recovery value of 30 percent, Velasco said in a report last week. Any restructuring probably wouldn’t take place before 2016, he said.

“Low entry points have the potential to generate positive returns in certain restructuring scenarios,” he said in the report.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen