Bondholders Are Doubting Venezuela's State-Owned Oil Giant

by and- How-long-can-this-last increasingly questioned amid shortages

- After $2.1 billion payment this week, next test is in October

Venezuela’s willingness to honor its debts is coming under fresh scrutiny even as the will-they-or-won’t-they jitters surrounding a $2.1 billion payment this week have largely subsided.

The bonds from the state oil company maturing Wednesday traded as low as 94 cents on the dollar last week, showing a lack of confidence that Petroleos de Venezuela SA would come up with the needed cash. The securities shot up to 97 cents on Friday after PDVSA issued a statement saying it had already begun the payment process.

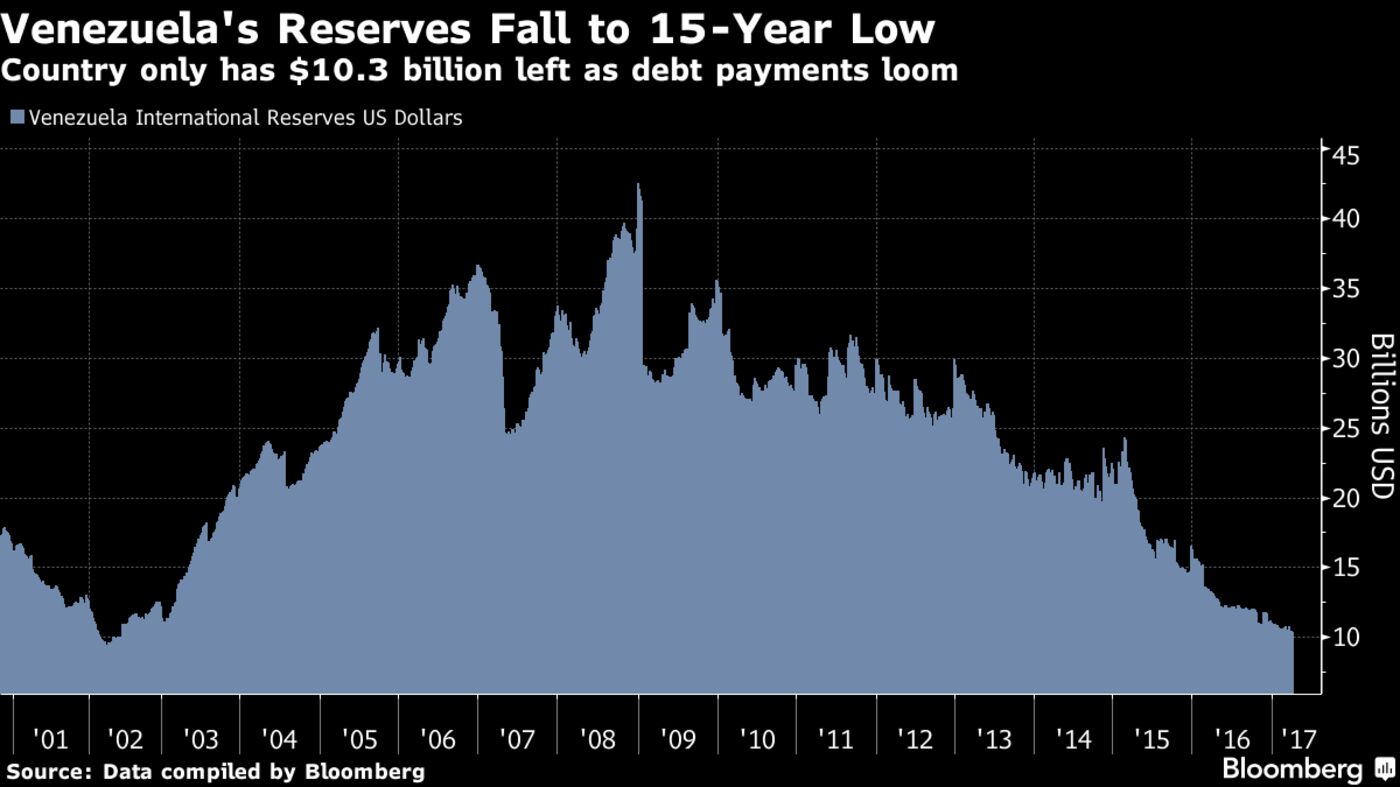

While analysts have been questioning Venezuela’s ability to avoid default for years, what’s different these days is increasing concern that a steady drop in foreign reserves will break the willingness to pay. The thinking goes that its diminishing supply of cash amid chronic shortages of basic goods means a default will happen eventually, so why should policy makers spend every last penny before succumbing to the inevitable? It would be better to stop payments now and renegotiate the debts, according to this line of thought.

“Now we’re entering into a more volatile, less predictable phase,” said Alejandro Grisanti, a former head of Latin America research at Barclays Plc who is now director of the Caracas-based consultancy Ecoanalitica.

Policy makers held an "intense debate" at a high-level meeting during the first weekend of April before the government agreed to continue with debt payments for the time being, according to a report from Ecoanalitica, which didn’t specify the source of the information. A spokesman for PDVSA declined to comment and an email to the Finance Ministry wasn’t returned.

The next big test for the country’s bondholders will come at the end of October and beginning of November, when PDVSA has about $2 billion in bond payments scheduled. Notes maturing Nov. 2 are trading at just 84 cents on the dollar, reflecting the skepticism.

Default Talks

While default talks have swirled around Venezuela on-and-off for the better part of two decades, bondholders have always gotten the money they were due even as prices for the oil exports the country relies on plummeted to about a third of what they once were and reserves fell from a peak of $42 billion in 2009 to just $10.3 billion now.

Venezuelan officials still say they have every intention of meeting their foreign obligations. In a speech last month, President Nicolas Maduro gave a passionate defense of his decision to pay back the debt.

“Do you think we would have been better off in default?” Maduro asked. “Let’s think of the national interest, of our land.”

Still, the pain is significant. The country is unable to import enough food, medicine and other basic goods to sustain its 30 million people. The economy contracted an estimated 10 percent last year, after shrinking about 7.5 percent in 2015. Protests are popping up everywhere, including the poor neighborhoods where Maduro traditionally found most of his support, and the government is cracking down on dissent as it seeks to consolidate power.

All the turmoil has investors betting there’s a 91 percent chance of default in the next five years, the highest in the world, according to trading in credit-default swaps. The strategy now for creditors is figuring out exactly when that last payment is going to be made, and then getting out quickly.

"If only anyone had a crystal ball and actually knew how long that would be, they could continue to do very well in Venezuela," said Jane Brauer, a strategist at Bank of America Corp.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen