Seven months after Ukraine declared its embattled economy would need debt relief, talks with creditors led by one of the world’s biggest fund managers are coming to a head.

The crunch phase in negotiations kicks off Wednesday in San Francisco, with the two sides still at loggerheads over how much of the burden should be forgiven. As Ukraine threatens to halt debt payments, the fate of billions of dollars of bonds rests in the degree to which they’re prepared to compromise.

Q: What’s Ukraine trying to do with its debt and why?

A: Ukraine wants to restructure $19 billion of foreign debt after the burden became too much following deadly street protests, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, a festering conflict in the nation’s industrial heartland and a plunging currency.

A: Ukraine wants to restructure $19 billion of foreign debt after the burden became too much following deadly street protests, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, a festering conflict in the nation’s industrial heartland and a plunging currency.

The restructuring is a condition of emergency assistance from the International Monetary Fund for Ukraine’s shrinking economy. Renegotiating the debt should save Ukraine $15.3 billion through 2018, according to the Washington-based lender, which is providing $17.5 billion of aid on top of bilateral loans from nations including the U.S. and Japan.

Ukrainian public debt, including state guarantees, jumped to 72.7 percent of gross domestic product at the end of 2014 from 40.6 percent a year earlier, the Finance Ministry estimates. State-run companies and banks must restructure $4 billion of debt to meet another IMF demand.

Q: Who are Ukraine’s creditors?

A: Unusually for a debt restructuring, Ukraine’s creditors are dominated by one company: San Mateo, California-based fund manager Franklin Templeton, which holds more than $7 billion of bonds.

A: Unusually for a debt restructuring, Ukraine’s creditors are dominated by one company: San Mateo, California-based fund manager Franklin Templeton, which holds more than $7 billion of bonds.

More unusual is that Ukraine’s second-biggest private creditor is a country: Russia bought a $3 billion Eurobond from it in December 2013, two months before street protesters ousted President Viktor Yanukovych. While Russia refuses to renegotiate the bond, deeming it official rather than private debt, Ukraine says its neighbor will be treated like other creditors.

The rest of the debt under discussion is mostly owned by 14 funds, according to Ukraine’s debt envoy, Vitaliy Lisovenko. Three of them — BTG Pactual Europe LLP, TCW Investment Management Co. and T. Rowe Price Associates Inc. — have formed a creditor committee with Franklin Templeton that owns $8.9 billion. TCW is being represented by Los Angeles-based fund manager Penny Foley, T.Rowe Price by Baltimore-based Mike Conelius, and BTG by London-based Igor Hordiyevych.

Q: How are negotiations going?

A: Not smoothly. The two parties have struggled to find common ground, with Ukraine pushing to write down as much as 40 percent of what it owes and creditors saying the nation’s goals can be met by extending bond maturities and trimming coupon payments alone.

A: Not smoothly. The two parties have struggled to find common ground, with Ukraine pushing to write down as much as 40 percent of what it owes and creditors saying the nation’s goals can be met by extending bond maturities and trimming coupon payments alone.

To shunt bondholders toward Ukraine’s position as talks stalled in May, lawmakers in Kiev gave the government the power to impose a moratorium on debt payments. Creditors say a writedown of the face value of the debt, often referred to as a haircut, would delay Ukraine’s planned 2017 return to international debt markets and raise costs when it resumes debt sales.

Negotiations gained traction in July after bondholders agreed to direct talks with Ukrainian Finance Minister Natalie Jaresko. They’ve so far proposed a 5 percent principal writedown, contingent on economic performance, which Ukraine countered with a new proposal of its own.

Jaresko, an American-born former investment banker, travels to California Wednesday to meet creditors, threatening to use the moratorium if this “last opportunity” to seal an agreement isn’t taken.

Q: How long does Ukraine have to reach a deal?

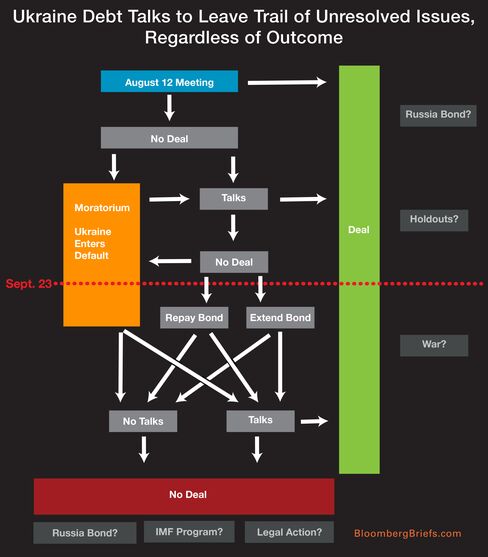

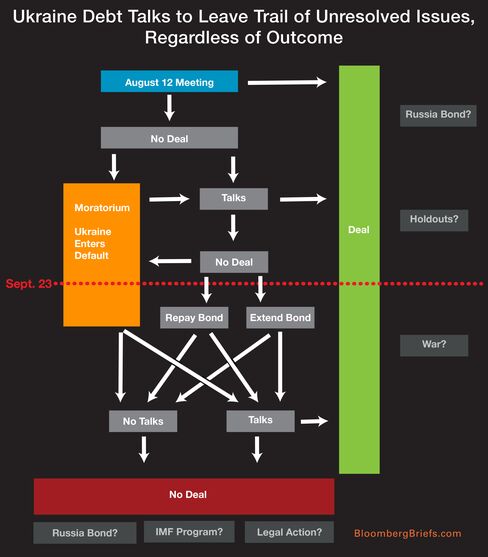

A: The deadline for debt talks is probably Oct. 3, after a 10-day grace period following a $500 million bond coming due on Sept. 23. If it isn’t paid in full or restructured by that date, Ukraine will default on all of its international bonds because of cross-default clauses.

A: The deadline for debt talks is probably Oct. 3, after a 10-day grace period following a $500 million bond coming due on Sept. 23. If it isn’t paid in full or restructured by that date, Ukraine will default on all of its international bonds because of cross-default clauses.

To restructure the bond by that date, Ukraine must agree to new terms with the Templeton-led creditor committee and call a meeting to allow the remaining foreign creditors to vote on the proposal. Bondholders must be given at least 21 days’ notice before the meeting can be held.

To change the terms on Ukraine’s bonds, 75 percent of bondholders must vote in favor at a meeting in which two thirds of creditors are represented. Quorum falls to one third at a second meeting if it isn’t reached first time around.

If a deal isn’t reached in time, Ukraine could ask holders of the September bond to extend the maturity by a few months, giving the sides more time to negotiate, or it could impose the moratorium until a deal is reached.

Q: What would happen if Ukraine defaults?

A: Ukraine’s international bonds contain cross-default clauses that mean missing a coupon or principal payment on one automatically results in default on all of them. The next chance for this to happen is Aug. 23, when a $60 million coupon payment is due.

A: Ukraine’s international bonds contain cross-default clauses that mean missing a coupon or principal payment on one automatically results in default on all of them. The next chance for this to happen is Aug. 23, when a $60 million coupon payment is due.

If the cross-default clauses are triggered, creditors would have the right to accelerate payment. Failure to pay would push Ukraine into arrears and trigger a credit event that forces banks to pay out on credit-default swaps, insurance contracts that protect the holder from non-payment.

Even if Ukraine is in arrears to private creditors, the IMF has said it would keep lending to the government. But the fund can’t lend to countries in arrears to official creditors, potentially complicating the bailout if the $3 billion Russian Eurobond is eventually designated as state aid.

Q: Has Ukraine restructured debt before?

A: Yes. Struggling as Russia’s currency crisis sank the hryvnia and swallowed central bank reserves, Ukraine renegotiated $2.5 billion of foreign debt and $300 million of domestic borrowing in four stages between 1998 and 2000.

A: Yes. Struggling as Russia’s currency crisis sank the hryvnia and swallowed central bank reserves, Ukraine renegotiated $2.5 billion of foreign debt and $300 million of domestic borrowing in four stages between 1998 and 2000.

Like now, the restructuring was backed by the IMF, and Lisovenko, at Ukraine’s Finance Ministry, conducted negotiations. While the government halted debt-service payments, there were no writedowns.—Marton Eder

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen