White House Sanctions May Scare Off Venezuela Vulture Investors

By- State oil company PDVSA’s five-year default odds climb to 99%

- Mnuchin says U.S. investors can’t restructure existing debt

U.S. Issues New Sanctions Against Venezuela's Maduro

The Trump administration’s ban on new Venezuelan debt could scare off so-called vulture investors by making it nearly impossible for the country to restructure its obligations.

That means in the event of default -- which investors view as pretty much a certainty within the next five years -- the country and its creditors may struggle to come up with an agreement that would assign any value to its outstanding bonds. It also will make smaller debt swaps much more difficult to get done, possibly hastening the day of reckoning.

Such restrictions may throw a wrench into the tried-and-true methods of so-called vulture investors, typically hedge funds that swoop into a country’s distressed debt shortly before or in the aftermath of a default with the goal of extracting value from bonds too toxic for most investors. These funds may now demand a much lower price if there’s no regime change that would prompt the U.S. to lift restrictions, largely because of the complications in negotiating a restructuring.

After Argentina defaulted on $95 billion of debt in 2001, hedge funds including NML Capital, a subsidiary of Paul Singer’s Elliott Management Corp., refused to accept restructuring offers and hounded the Kirchner government for payment in U.S. courts. A decade-and-a-half later, Argentina reached a settlement with the majority of bondholders. But the Trump administration’s executive order on Venezuela would prohibit the Singers of the world from suing and demanding payment with new bonds as they did in Argentina.

Because a default with no hope of restructuring would expose the country to international lawsuits and seizures of its assets, it could increase the chances of a regime change in the aftermath of a missed payment, according to Shamaila Khan, the director of emerging markets at AllianceBernstein, the ninth-largest holder of Venezuelan sovereign debt and 12th-largest holder of the state oil company’s bonds as of June 30.

That would presumably be well received by the Trump administration, which has sought to crack down on President Nicolas Maduro because of what his critics see as his efforts to undermine democracy. Maduro is seeking to rewrite the constitution in a way that would sideline the opposition and solidify his grip on power in a country beset by a political crisis, rampant inflation, a collapsing economy and shortages of affordable food and medicine.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said on Friday that "there will be no transactions with U.S. investors for new debt, including restructuring existing debt or extending maturities without specific licenses being issued."

Late the same day, Maduro asked holders of Venezuelan bonds to meet with Economy Minister Ramon Lobo this week to discuss the effects of the U.S. sanctions. U.S.-based holders of Venezuela bonds will be hurt the most by the penalties, Maduro said. Donald Trump “burned the bonds in their hands” by trying to harm Venezuela, he said.

Although many traders may bet that the bond restrictions will increase Venezuela’s default odds, the Maduro government’s inability to restructure debt may, ironically, lower the chances it won’t pay, according to Francisco Rodriguez, the chief economist at Torino Capital in New York. His thinking is that prior to these new sanctions, the administration may have seen restructuring as a way out if things got even more dire. Now that they can’t restructure, their task is much simpler: Just keep paying, one month at a time.

The additional penalties strengthen Maduro’s argument that his nation is under attack from outside interests, likely pushing him toward lenders of last resort in China and Russia, Diego Ferro, the co-chief investment officer at Greylock Capital Management, which specializes in undervalued, distressed and high-yield assets, said Friday on Bloomberg TV.

"I don’t think it’s going to have much of an impact because Venezuela cannot raise money in international markets anyway," he said.

99 Percent

The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control has traditionally interpreted sanctions broadly, so any attempt to circumvent their objective by clever structuring of a debt deal would be risky, according to Lee Buchheit, a partner at financial-market law firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, which advised Ecuador and Argentina on their sovereign debt restructurings.

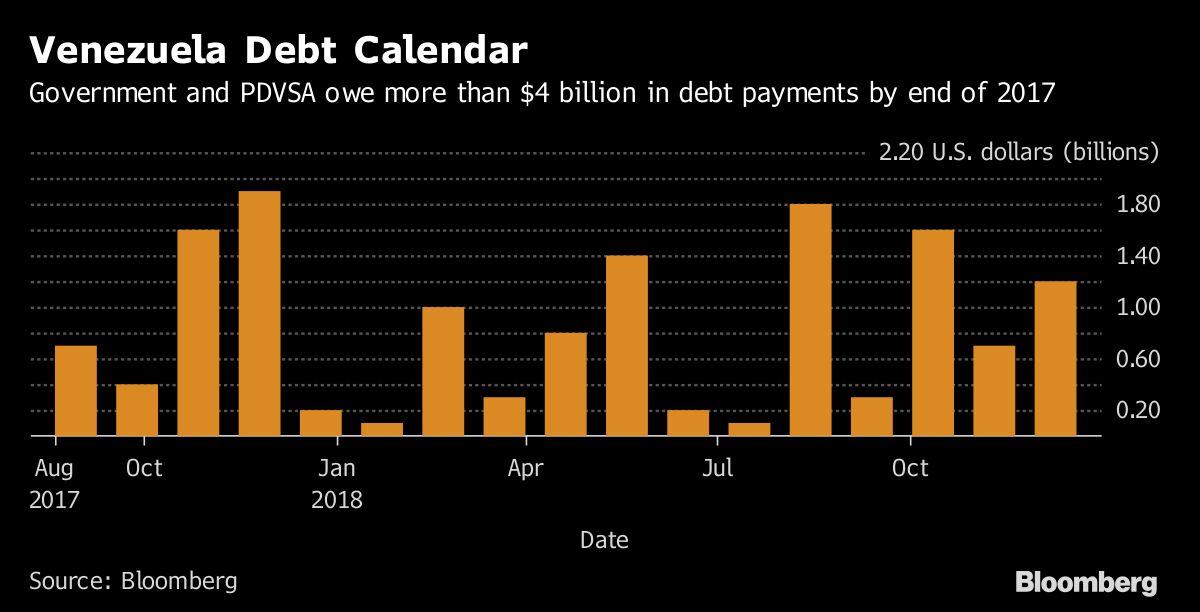

The implied probability of Venezuela missing a debt payment over the next 12 months dropped to 63 percent on Friday from 66 percent the week prior, according to credit-default swaps data compiled by Bloomberg. Still, over the next five years, the odds of a sovereign credit event rose to 96 percent and Petroleos de Venezuela’s default probability hit 99 percent.

Moody’s Investors Service said on Friday that the latest round of U.S. sanctions increased the refinancing risk on PDVSA’s debt due in October and November, bringing the company even closer to a credit event in coming months.

"The next shoe to fall may be Maduro’s reaction to the sanctions," Buchheit wrote in an email. "He could seize upon them as a justification for ceasing his policy of full debt service."

— With assistance by Katia Porzecanski

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen