History Shows Even Sovereign Bond Default Won’t Unseat Maduro

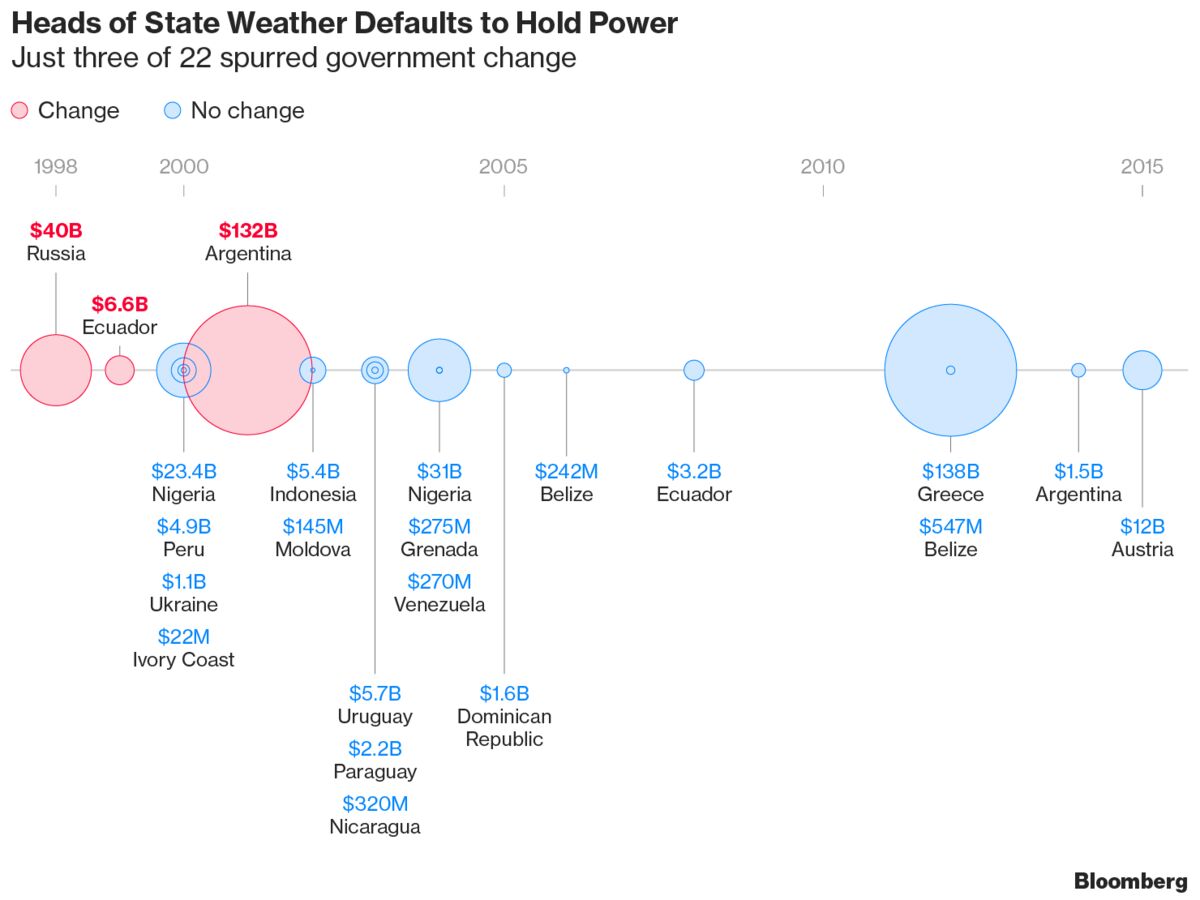

By and- Under 15% of defaults since 1992 spurred government change

- Maduro could ‘stay in power through it all,’ Reinhart says

Nicolas Maduro

Photographer: Carlos Becerra/Bloomberg

Venezuela has a dubious backstory when it comes to paying sovereign debt. It’s tied with Ecuador for the most defaults since 1800.

But for anyone betting that a default would catapult President Nicolas Maduro from office even as he holds on in the face of untold economic misery, here’s a more relevant marker: Not once on those 10 occasions, most recently in 2004, did a missed payment spur a change in government.

In fact, defaults around the globe have triggered governmental change less than 15 percent of the time since 1992, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. In Venezuela’s case, Maduro has enough support from the nation’s powerful military to weather any fallout, said Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart, co-author with Kenneth Rogoff of “This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly.”

“If you don’t have to listen to voters because you’re installed through military might, there’s no reason why a default would mean a change in government,” she said by phone from Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Venezuela is beyond democratic solutions, so Maduro could very well stay in power through it all.”

For most traders, a Venezuelan default is all but certain. The implied probability of one occurring during the next five years has climbed to 98 percent from 91 percent a year ago, according to credit-default swaps data compiled by Bloomberg.

Venezuela’s benchmark dollar bonds due in 2027 rose Thursday to a one-week high of 39.47 cents on the dollar as of 11:30 a.m. in New York.

‘Death Sentence’

Knossos Asset Management, the Venezuelan-dedicated hedge fund known to make big bets on the nation’s debt, parked 90 percent of its portfolio in cash this summer, citing concern that a default would spur regime change. It reasons that investors would seek to seize state-owned assets such as oil, which accounts for 95 percent of the country’s export revenue, making it all but impossible for Venezuela to import basic goods and services that are already in short supply. Danske Capital, the 18th-largest reported holder of Venezuelan bonds, has said a default would be the “death sentence” for Maduro’s administration.

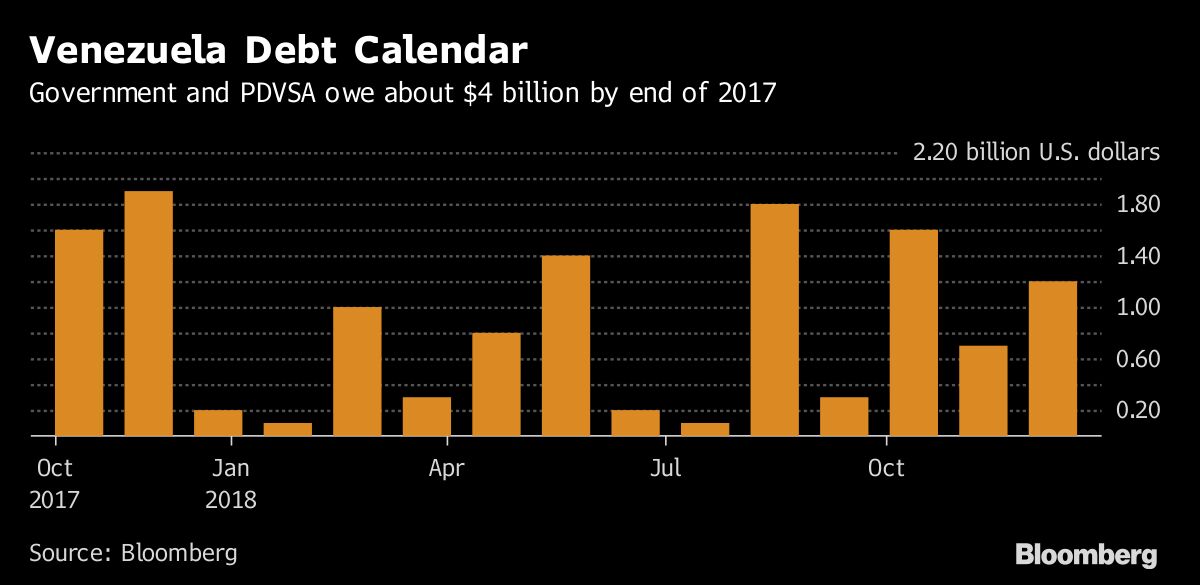

Some $3.5 billion in debt payments come due by November on about $70 billion owed by the government and its state oil company.

“A default will bring about a change in government,” said Francisco Ghersi, co-founder of Knossos. Government officials "would be entering a new territory that is so complex that they wouldn’t be able to manage."

Others are aiming at an extended horizon. Money managers from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to Grantham Mayo Van Otterloo & Co. scooped up more longer-dated Venezuelan bonds this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The thinking among some bond buyers is that a new opposition-controlled government could negotiate a restructuring that’s would pay them generously. “Both bondholders and the new government have an incentive on both sides to restructure the debt and also attract investors to the economy,” said Shamaila Khan, the director of emerging markets at AllianceBernstein LP, the ninth-largest reported holder of Venezuelan debt.

Revolving Door

If Ghersi’s right, it wouldn’t be the first time default led to a leader’s downfall.

After Russia defaulted on $40 billion of debt in August 1998, the ruble lost more than half its value in six months. From that economic wreckage emerged a former KGB intelligence officer from St. Petersburg named Vladimir Putin.

Months after Ecuador missed a payment on U.S.-backed Brady bonds in 1999, President Jamil Mahuad was overthrown by the nation’s most powerful indigenous group and military officials. And when Argentina defaulted on its international debt in December 2001, La Casa Rosada became a revolving door, featuring five presidents in 10 days. The last of the quintet’s leaders, Eduardo Duhalde, survived just a year.

Still, causality is often difficult to prove, according to Martin Uribe, an economist at Columbia University.

“In Latin America, especially, because many democracies are still very young, you see a strong association between a large economic crisis and the demise of political administrations,” he said by phone from New York. “But if the Maduro administration falls, was it the economic crisis or the weakness of the regime? It’s not easy to disentangle.”

Jailed Presidents

Under the majority of defaults, from Nigeria to Nicaragua, heads of state have survived. When a missed payment has coincided with a government change, it’s often been corruption, not default, that brought the leader down, as was the case with Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori and Paraguay’s Luis Gonzales Macchi. Both were later jailed.

In Venezuela’s case, if triple-digit inflation, dwindling crude output and eroding foreign reserves can’t unseat Maduro, neither will a default, according to Francisco Rodriguez, the former head of Venezuela’s congressional budget office who is now chief economist at New York-based Torino Capital. Since an authoritarian leader’s survival often hinges on control over resources relative to the rest of society, Maduro may actually come out of a default stronger, he said.

Should Maduro cling to power after a default, traders would be in a challenging position, because sanctions by the Trump administration prohibit U.S. investors from restructuring existing debt. For now, he’s proven resilient.

“The Maduro regime is staying in power through extreme conditions,” said Harvard’s Reinhart. “There’s no reason to expect more extreme conditions being the factor that topples him.”

— With assistance by Samuel Dodge

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen