Let’s go back in time — to May 2014. Deutsche Bank was in the market to raise capital, including at least €1.5bn of additional Tier 1 capital securities. Or CoCo (short for contingent convertible) bonds.

Deutsche ended up issuing €3.5bn, on €25bn of demand. Quite a few investors must have liked the sound of the bonds’ 6 per cent coupon.

Hopefully they came to that conclusion after perusing the prospectus. Especially this bit, on deferring coupon payments if the accounting-related amount available for distributing them (not the same as Deutsche’s overall capital or liquidity) isn’t enough.

(This is before looking at write-down / conversion, in the event of the bank’s capital ratio being too low. This feature is why we’re using the CoCo term for the bonds as well as AT1. Blast us in comments if you’d see them differently.)

Of course, you’ll probably know AT1 bonds like these better for having left the market agape in the last couple of days.

On Monday for example, they were being marked at 70 to 75 cents on the euro. That seems to price in Deutsche (or its “competent supervisory authority”) not authorising a coupon payment this year nor for some time to come, which seems pretty extreme.

For want of liquidity in what they actually bought, some investors even bought protection on Deutsche’s senior bonds. These won’t pay out if the CoCo debt, submerged far below in the bank’s capital structure, is triggered, but the CDS move may confuse outside observers who think that it’s a rational signal about Deutsche’s credit. Which seems to lend even more of an air of artificiality to CoCo investing.

How many investors really did understand in May 2014 why they might not get that 6 per cent coupon?

How many knew that this particular Deutsche CoCo made it especially difficult to price that risk?

We ask because it was actually quite well explained at the time — by our own Tracy Alloway, as it happens, and by the European credit analysts at Bank of America.

Here’s a relevant section of their 16 May, 2014 note on the bonds. Emphasis ours:

DB’s new AT1s would add an additional level of complexity to the issue of whether or not AT1 investors receive their coupons, we think. In some ways, if these trades ever print, we’ve crossed the Rubicon – and not in a good way. So, we are writing about this transaction because as we were considering the format of the transaction,we became aware that it was raising a number of issues of wider relevance to the AT1 market (and of course to DB as a credit) that have received less focus in prior transactions than perhaps they should.As is well known, European banks have to operate within the strictures of the CRD 4 Combined Buffer Requirement/Maximum Distributable Amount (CBR/MDA) regime. That is, if for whatever reason a bank pierces its CBR, there are likely to be restrictions on its distributions and the deeper the piercing of the CBR, the greater the restrictions are likely to be, because the smaller the MDA is. DB also operates within this regime…DB AT1s have an additional hurdle: that of Available Distributable Items under German GAAP/Law. These are merely the distributable reserves that any German company holds for distribution, as per the unconsolidated accounts under German GAAP. Our view is that the disclosed ADI for DB is much smaller than the CBR/MDA buffer – it’s only €2bn. And in contrast to the CBR/MDA discussion which the market has effectively (we think) said isn’t relevant today because it’s for the future, the ADI is active right now…The capacity for payment of AT1 coupons is ‘Available Distributable Items’ under German Unconsolidated GAAP – numbers that we haven’t really considered from DB before and which unfortunately the bank has yet (as far as we could discern from the investor call) to promise to disclose in an accessible way on a regular basis. We think the transparent disclosure of this number under German GAAP is a key consideration for whether investors get their coupon.

Well the good news is that Deutsche’s disclosure has improved.

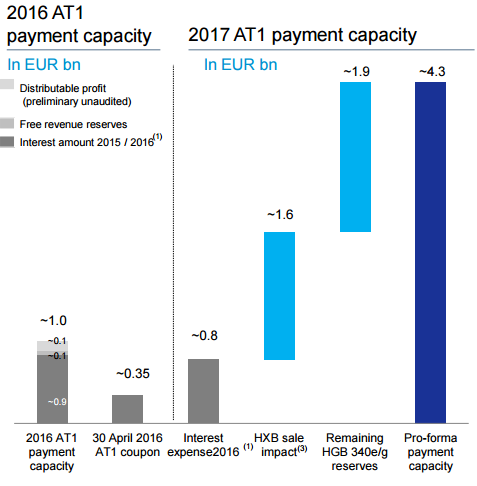

It has €1bn capacity to pay this year’s €350m coupon (click chart to enlarge).

The bad news is the bond price was still close to 70-75 cents on Tuesday.

Which suggests a philosophical predicament for CoCos.

There is the matter of Deutsche’s predicament over its profits, of course. Investors have to work out whether Deutsche’s plans for capital and earnings in the long term make future coupons a safe bet. That might include everything from assessing the sale of a stake in a Chinese bank, to the possibility of BNP Paribas-style regulatory fine inflation, to rating the pep talks of retired US Army General Stanley McChrystal.

More broadly though, the Deutsche episode seems to add fuel to an old argument that CoCos aren’t bonds, or even hybrids. As Dan Davies suggests, maybe it is more appropriate to think of them as a regulator-optimised form of preference share.

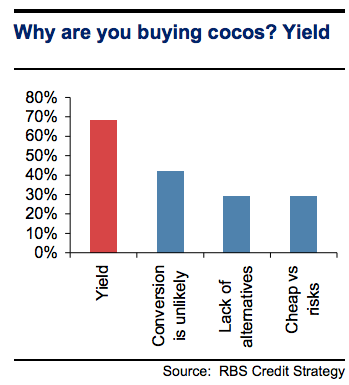

But if you put it like that, it might make the bank bond investors of just a few short years ago look like yield-chasers.

And that wouldn’t be true. Would it?

Chart via RBS — also from 2014.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen