Hedge Funds Line Up Against Mozambique in Tuna Bond Battle

by and- Bondholder group says won’t negotiate before IMF deal reached

- Mozambique wants to restructure debt before talks with IMF

Hedge funds and some of the world’s biggest emerging-market bond investors are girding for a fight with Mozambique and its other creditors.

The country’s attempt to reach a restructuring agreement by the end of the year suffered a blow when a group of five investors, who hold 60 percent of its $727 million of Eurobonds, said the notes should be treated differently from loans to two state companies and talks couldn’t begin until an International Monetary Fund program was in place. Mozambique wanted to negotiate with creditors as one group, while the Washington-based lender has said a deal with the bond and loan holders should come first.

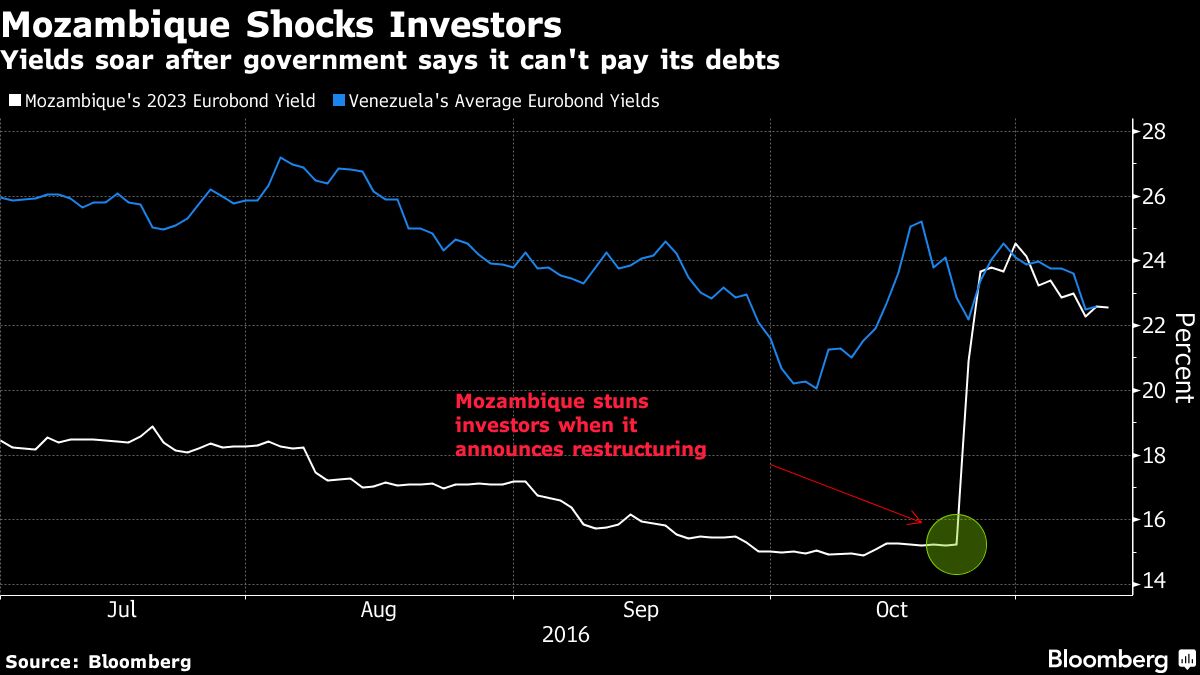

The move by the investors, who include Franklin Templeton and New York-based hedge fund Greylock Capital Management LLC, came two weeks after the government said it needed to restructure around $2 billion of foreign debt, including the Eurobonds, which were sold barely six months ago in a swap for more expensive debt owed by a state tuna-fishing business known as Ematum. Yields on the sovereign securities, due in January 2023, soared by more than 900 basis points to almost 25 percent and overtook Venezuela’s to become the highest in the world.

“It’s not the fault of bondholders and they shouldn’t expect any willingness by us to accept” writedowns, Lutz Roehmeyer, who helps oversee about $12 billion in assets at Landesbank Berlin Investment, including Mozambique’s Eurobonds, said by phone. “They should go into default on those loans to the state companies. There’s no need to pay the loans on time.”

Here’s what’s at stake and what might happen next:

What happened?

Mozambique, one of the world’s poorest nations, went from being laudedtwo years ago by the IMF’s Managing Director Christine Lagarde to being ravaged by a combination of excessive borrowing, plummeting commodity prices and delayed investments in massive natural gas fields. The crisis worsened in April when the IMF and other donors cut aid after they discovered around $1.4 billion of secret loans issued several years ago by two state firms, Proindicus and Mozambique Asset Management.

Is Mozambique really in bad shape?

Finance Minister Adriano Maleiane was “visibly stressed” when he made a presentation to investors on Oct. 25, according to Anne Fruhauf, an analyst at New York-based Teneo Intelligence. Public debt has rocketed from 40 percent of gross domestic product in 2012, the year before Mozambique took on the loans, to 113 percent, higher than anywhere in sub-Saharan Africa apart from Eritrea and Cape Verde, according to the IMF. Mozambique forecasts its net foreign reserves will be $1.1 billion next year, down almost 60 percent from 2014.

The government said it would have no money left over for debt payments in 2017, which include a $60 million coupon on the Eurobond due Jan. 18. In Maputo, the capital, many stores are empty and Mozambicans are battling inflation of 26 percent. Since the start of 2015, the local metical has lost 58 percent of its value against the dollar, making external debt more expensive to service.

“Mozambique is in a really, really difficult place,” Alex Vines, head of the Africa Program at London-based Chatham House, said in an interview in Johannesburg on Nov. 4. “They’re on this cliff-edge. They don’t have money.”

Who’s involved?

The creditor group comprises Franklin Templeton and AllianceBernstein LP, which between them manage $1.2 trillion of assets, and three hedge funds: Greylock and NWI Management LP, both New York-based, and London’s Pharo Management LLC. They called on other bondholders to join their group, but said it will be closed to the loan investors. Charles Blitzer, who spent 8-1/2 years at the IMF, most recently as assistant director in the capital markets department, is advising the bondholders.

The loans to Proindicus and MAM, due in 2020 and 2021 respectively, were originally provided by Credit Suisse Group AG and Russia’s VTB Group, though the banks syndicated some of the debt. Mozambique is being advised by Lazard Freres, an investment bank, and law firm White & Case.

What is Mozambique trying to do?

“They need to buy themselves time,” Phillip Blackwood, a managing partner at EM Quest Ltd., which advises Denmark’s Sydbank A/S on about $2.5 billion of emerging-market assets including Mozambique’s bonds, said by phone from London.

What happens next?

Mozambique hoped to talk to investors this month before concluding a framework for a “debt resolution proposal” in December, according to the presentation. That was meant to help it negotiate new funding from the IMF early next year. The formation of the creditor group and its demands mean that timetable probably won’t be kept.

“There’s not a basis for trust,” said Roehmeyer. “I think it’ll take roughly half to three-quarters of a year to sort out.”

The bond group has also said that it won’t start talks until an audit of Proindicus, MAM and Ematum is completed. The government has chosen New York-based risk analysis firm Kroll to carry that out.

What are Mozambique’s options?

A spokesman for the Finance Ministry said Nov. 3 in an interview that the government wants to extend its maturities to 2023 and 2024, rather than impose outright losses on creditors. A day later, the ministry backtracked, saying in a statement it was looking at all options.

The bondholders, who say they already made a concession earlier this year when they agreed to swap out of the Ematum notes into the longer-dated Eurobond, seem in no mood to back down. Some are also calling on Mozambique to cut its spending.

“The holders of the Eurobond are on firmer footing because they’ve already taken a restructuring, whereas the loan holders haven’t,” Blackwood said. “The loan holders really need to restructure and push out their payments, as the bondholders already have. Mozambique also has to make some budget cuts. It can’t just say that there’s no money left.”

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen